The Advocate has an interesting, if brief, blurb on the illustrator Robert Riggs today. Riggs, not known to have been gay but clearly influenced by gay male artists of his time, sketched and painted oversized male bodies in dramatic, hyper-masculine scenarios (boxing, baseball, hunting, warring). His work appeared in Life, The Saturday Evening Post, and Argosy.

The Advocate says:

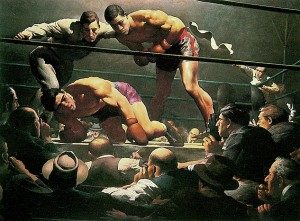

There is a grimness to his work, like an underlying threat […] Riggs’s work has a tension that verges on frightening, like the electric moment right before violence erupts.

What strikes me about both this work and how it’s described here is the complete erasure of the kind of anxieties that animate any of the dozens of think-pieces written about lumbersexuals in the last year. Chief among these concerns is the idea that privileged, young, urban, hetero men are embracing the trappings of working-class labor (beards, flannel, work boots, cheap beer) without acknowledging or challenging the structures that enable them to borrow without doing the actual work. It costs nothing to grow a trimmed beard.

From my perspective, such criticism demands of masculinity an authenticity we would never comfortably expect of post-feminist women. Jezebel’s foray into the conversation is even titled “Who is the lumbersexual and is anything about him real?” As Peter Lawrence Kane articulates in one of the more insightful enquiries into the phenomenon, the lumbersexual would have been unthinkable without the metrosexual revolution of the early-00s. “Around the time men who previously just thought of themselves as men began thinking of themselves as straight men,” Kane writes. Both using beard oil and tszujing in the manner Carson Kressley taught to straight male viewers are ways of performing a decentered masculine identity.

To that end, it’s notable that Riggs’s cartoonish male forms are mostly engaged in homosocial spectacles. The image above, titled The Brown Bomber, presents Joe Louis knocking out Max Schmeling in 1936. They appear in an elevated ring, their muscles and sweat high above the press and the crowd. There is no doubt that what is taking place is not an essential aspect of masculinity; rather, it is a performance of one version of “man” for the entertainment of other men. One could not imagine the balding reporter in the image’s center performing in the same manner. Similarly, other Riggs illustrations of baseball players and hunting parties resplendent in ceremonial dress emphasize the considered, affective dimensions of even the most hetero-normative visions of masculinity. One may critique the privilege of office workers dressing-up as laborers, but Riggs’s work ought to remind us men have been dressing-up in one form or another forever.